How to tell the difference and why it matters- from the National Audubon Society.

Research shows that native plants can help create a healthier ecosystem that supports a higher diversity of wildlife. The plants we choose for our yards, gardens, and public spaces have a huge impact on birds, yet so much of ornamental landscaping is dominated by non-native species.

How do we know what to replace? Differentiating between native plants, non-native plants, and invasive plants can be both simple and nuanced. We break it down for you, and provide some alternatives to plants you might have in your backyard or local box store.

Native: Native plant species are species that have existed historically in that area. The Plants for Birds program deliberately say these are plants that have existed in a location prior to European colonization in North America.

“For the Plants for Birds program, we say it is any plant that here before European colonization,” says Partnerships Manager for Plants For Birds, Marlene Pantin. “And then of course native plants are those that are adaptable to the climate, and the soil conditions in that area.”

Non-native: Non-native plants are species that have not existed historically in one area but have been introduced due to human activities. Non-native plants don’t necessarily pose a threat to native plants, but as mentioned before, non-native plants may not support ecosystem health as well as native plants do.

“Even within North America a plant can be native in portions of it and non-native elsewhere, says Rowden. “When talking non-native plants, for example here in California, it’s not only plants that we brought in from Asia or Europe or wherever—it’s also the plants that were brought here from the East Coast, or even just east of the Rockies. Historically, the Rockies were the boundary that plants couldn’t cross but then humans brought them.”

OK, so what about “invasive” plants? According to Rowden and Pantin, invasive plants are those that were either intentionally or accidentally translocated to an area where they did not exist naturally, and where they cause harm to native plants and the local ecosystem.

Invasive: Invasive plant species are non-native to particular ecosystems and the introduction of them is likely to cause “economic or environmental harm or harm to human health,” according to the National Invasive Species Information Center.

For Pantin, invasive species are species that disrupt the growth of native plants, and root and spread quickly. Rowden agrees with Pantin and goes further to say that these species usually do not have any ecological checks on it, which means no predators, pathogens, or any of those sorts of things that can ecologically speaking, keep a species from spreading.

Examples of invasive species in your yards to replace.

Let’s get it right out there off the bat: the struggle to plant only native plants is real. “People go to the big box stores, and they buy plants that look really pretty, and they may be wonderful plants, but they aren’t native to that particular area,” says Pantin. Box stores have very little incentive to carry native plants, and especially to be mindful of what plants might be native to where that particular store might be.

Tatarian Honeysuckle: Invasive honeysuckles are often larger than their native counterpart. These honeysuckles produce a large amount of seed and fruit that can be easily disseminated by birds. This plant can shade out many native plants and compete for pollinators, which can reduce the formation of fruits and seed from other native plants.

If you are in the eastern United States, you can replace the shrub honeysuckle with coral honeysuckle.

Greater Periwinkle: Common around the United States, the greater periwinkle outcompetes other plant species and prevents the establishment of native species, the plant is difficult to control because of how aggressive it spreads.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife suggests the native alternative, Douglas iris.

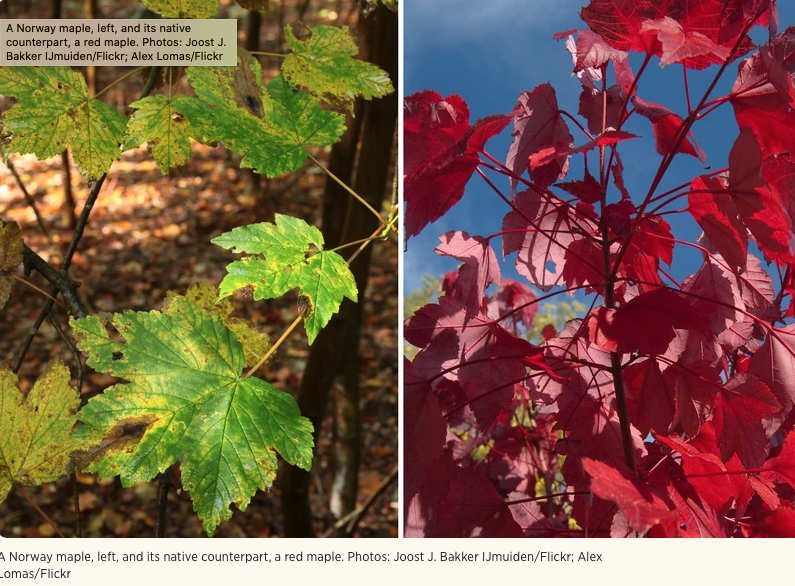

Norway Maple: The Norway Maple is a popular tree to plant along streets and in lawns, and is a shade tree. However, being a shade tree, it makes it difficult for any native plants to grow in the understory below.

A replacement for this tree could be the Red Maple, which is native to the eastern United States, ranging from Maine to Texas.

Want to know more, and find plants that are native to your area? Check out Audubon’s Plants For Birds database. Not only will the database tell you what plants to buy and which birds those plants will support, it will also show you where you can buy them. Your local Audubon chapter can also help you find where to buy native plants, and many hold their own local native plants sales. Love shopping online? Check out the many native plant species offered by Audubon’s native plant retail partner, Bower & Branch.

For more information and other articles related to the environment and birds: https://www.audubon.org/